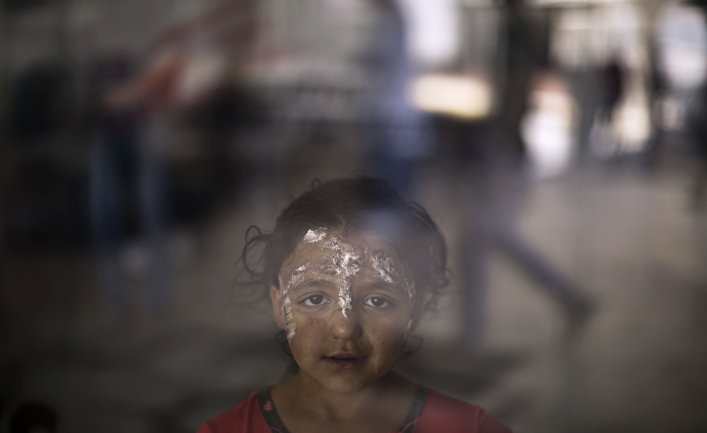

Just seconds ago you were on an Emergency Ward — in a hospital for those wounded in the war in northern Afghanistan. It's a neutral hospital. They treat everyone here, no matter what side they fought on, and no-one is considered a soldier while they're in the hospital – by international convention. The hospital provides help for hundreds of thousands of people – last year alone, 22,000 people turned here for help. There are no weapons here – only doctors, nurses, and those who need their medical care. All are accepted – no matter what they do, or say.

But then – sixty minutes of hell. The howl of attacking aircraft is a familiar sound – yet although there were many all day, this one purposely buzzed the hospital before dropping its bombs, and then flew off to repeat its strike. Again and again, hour after hour. It made no difference that the hospital staff made desperate calls to the Americans, to say there was some appalling mistake in the targeting… nor did it make a difference that everyone in the entire area knew that this was a Doctors Without Borders (DWB) hospital. DWB, a Nobel Prize-winning organization — with no skeletons in the cupboards. It simply treats sick and wounded people, doesn't get involved in politics, and stays out of conflicts — unless conflicts come visiting.

#Kunduz We were treating combatants as well as women & children. A patient is a patient https://t.co/TA59r6uCP8 @MSF pic.twitter.com/NTeK0Avbxa

— MSF International (@MSF) November 5, 2015

There were thirty fatalities in the attack, which also destroyed the hospital and left it unable to do its work. Amongst the victims, thirteen were hospital staff, ten were patients whose bodies it was possible to identify, and a further seven corpses were so badly mutilated that they were unidentifiable.

A month has now passed since that calamitous day for Doctors Without Borders, for military hospitals, and for all that hospitals should represent. The clangor of exploding shells no longer rents the air, but instead a raft of unanswered questions remains. Why did the USAF C-130 aim its devastating weaponry at a hospital? What went wrong? What had they intended to achieve? What did they think was located there? It was not news for anyone that there were Taliban patients at the hospital. Kunduz had been taken just days before, and remained in Taliban hands. Doctors don't ask who a patient fights for. They simply see wounded people, and treat them. Within the hospital, the war stops. Weapons and wars remain outside its walls.

We are publicly releasing an internal document with a view from inside our #Kunduz hospital https://t.co/KZufLLbmoS pic.twitter.com/RiQJdVZhLS

— MSF Canada (@MSF_canada) November 5, 2015

“We were located there with the agreement of all sides, and we kept our hospital fully under control” explains Michael Hoffman, head of the Brussels Office of Doctors Without Borders – currently involved with the issue of the attack on the Kunduz hospital. “Our neutrality was assured. The only people in the hospital were the patients, and 85 medical staff, of whom 9 were foreigners. At the time they bombed the hospital, there were two surgical operations in progress.” After the bombing, there isn't a single emergency medical facility in the entire area – and no-one can say when it will become possible to rebuild the bombed Kunduz hospital.

“We don't say that the hospital will not be rebuilt — but that's going to take months” says Hoffman, “and that's only to assemble all the necessary medical equipment from abroad. But most importantly — we need to know how this happened? Until we get an answer to that question, we cannot go back there. We have to understand the rules that apply in this war. From our point of view, it would be reckless to post more people there, and send them directly into the firing line once again.”

#Kunduz First room to be hit was ICU where patients were immobile. They burned in their bed https://t.co/TA59r6uCP8 pic.twitter.com/yAh4FKfTlT

— MSF International (@MSF) November 5, 2015

Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) received an apology from US President Barack Obama, and from the American armed forces – but these apologies included no explanation of what occurred. The Afghan authorities initially claimed that shooting was coming from the hospital which prompted a request for air support – since there were Taliban in the hospital, and even a valuable Pakistani spy. But the facts are that this story, just like others in which hospitals have come under fire, calls for answers. Médecins Sans Frontières has demanded an immediate investigation. The organization has the right to drill down to the underlying truth, because the borderline between military operations and war crimes has been broken once again.

But the silence these demands receive is telling. “We've asked the governments of 76 countries to support our case for an independent investigation – to find out what happened, and prevent another tragedy… but all we've had from them is an awkward silence. Surely it's understandable, that we want to get to the bottom of this?” asked DWB President Joanne Liu.

Medics were shot from the air as they ran between buildings during U.S. strike on hospital in #Kunduz, @MSF says: https://t.co/uLgxXgJVOj

— CNN International (@cnni) November 5, 2015

At the time of the Kunduz attack, a month ago, Afghan forces were being asked to support the American effort to regain control of the city. They had the map coordinates of the hospital, which has been running there for over four years. The hospital is the only building in Kunduz where the lights are on at night. The DWB logo is painted on the roof of the building. It's not possible to make a mistake. Even if we accept that mistakes are inevitable in war, there are still limits – and only an independent inquiry will reveal if those limits were broken in this case.

Just a week ago, yet another DWB hospital was hit by missiles – in Saudi Arabia, where there has been fighting against the Huthi rebels. Last year, a number of patients were killed by pistol-fire while they lay in their own hospital beds in Southern Sudan. “It's our view,” Hoffman says “that even in time of war there are rules, and that these rules need to be reconfirmed, for the sake of everyone's safety.”